Let’s get In an elevator together and go down, down, down, in time, to the early 1980’s and Seattle’s burgeoning music scene. This isn’t a story about Nirvana, Pearl jam, Kenny G, or other Seattle acts whose names are hung in the stars. Nope, this story happened at a much lower altitude, closer to the ground, where the rest of us were. Seattle had another music scene that seldom gets covered. It was a gritty, beer-soaked, smoke-filled, neon-lit bar scene, with a lot of great bands most folks have never heard of.

I left Vancouver Canada and showed up in Seattle in the fall of 1981. A young skinny kid with a Fender Stratocaster, a Super Reverb amp and a hunger in my belly for the stage.

Once I got there, I became an avid reader of the Seattle rock music paper The Rocket. Any musician in Seattle who didn’t get the current copy of this publication was out to lunch. Through The Rocket I became aware of a local band called The Rangehoods. I’d seen their name around for a while, but I’d never made it to one of their gigs until the year I saw them at Bumbershoot, Seattle’s Labor Day Music Festival. I looked through the schedule and at dusk on a warm Saturday night, I walked into the venue where they were playing. At the front of the band was a guy named Steve Pearson. He had a cool haircut and he stood about six feet tall. He was long and lean and dressed in jeans with cowboy boots and a cowboy shirt. Slung across his shoulder was the coolest Gibson guitar I’d ever seen.

The gold tail-piece was engraved with the name Super 400. The Super 400 is fairly rare compared to other models. It was not produced in big numbers. Some years, Gibson only made a few. It’s a looker though, with a large hollow body, featuring two F-holes and two large electric pick ups. Its natural finish showed the beautiful grain of the wood on its sides and its hand-carved arched-top. In between the strings on the headstock of his guitar, Steve had tucked a lit cigarette, still smoking. Every now and then he would reach over and grab the cigarette out of the guitar strings, smoke it for a while, and then put it back in the strings mid-song.

He was handsome like a young Humphrey Bogart and naturally cool without being too much of a poser. On the guitar stand right behind him was another Gibson Super 400 at the ready in case he broke a string, went out of tune, or just wanted to switch guitars. Standing next to Pearson was his partner in crime, Pat Hewitt who was also playing a Gibson Super 400. Pat also had a smoking cigarette tucked into the strings of his guitar’s head stock. On the guitar stand behind Pat, was yet another Gibson Super 400, bringing the on-stage total to four.

It’s my humble opinion that prior to the Rangehoods, in the entire history of the world, no one had ever seen four Gibson Super 400s on a single stage at the same time, anywhere. Ever. Therefore, in my mind, the Rangehoods won a contest of cool that nobody else even thought to enter. When it came to creating a cohesive stage-vibe, these guys brought something else, a unique visual legitimacy that sold the band to the audience in an instant. Both Pearson and Hewitt were playing these hollow-bodied beauties through VOX AC-30 tube amplifiers from England. They were loud and right on the verge of feedback most of the time. The guitars growled with a warm wooden howl. Any music fan who wasn't convinced by the sounds they were producing could just look at their guitars and be amazed. Giant hollow-bodied guitars and tube amplifiers are powerful weapons in the right hands. Right behind them was their drummer Don Kammerer, a well-seasoned Seattle rock veteran with short black hair and a crisp, hard-hitting beat. Over the years he’d share the drumming duties in this band with a Seattle drummer named Billy Shaw, who became one of my best friends. For more information on Billy, check out one of my other podcasts called: The Ballad Of Billy Shaw.

The bass player was a no-nonsense, serious looking guy named Bruce Hewes. Bruce was ruggedly handsome with longish black, curly hair. He played his bass effortlessly and had it slung so low that his unbent right arm and picking fingers, touched his bass strings just above his right knee. Hewes had a lonesome danger in his eyes that gave a sense of urgency to their performance. He was a little too handsome to be an inmate and too rough-cut to work in an office. They had their own powerful and jangly sound with Pearson’s great songs like “Chip On My Shoulder.” The audience hung on every phrase of the song and sang along with his catchy chorus. It sounded like a song that should be in high rotation on the radio.

Pearson’s voice rose above the band in a high raspy tenor. Hewes and Hewett added the harmonies. The guitars, the cigarettes, the roar of their AC-30s all produced a loose, whiskey-fueled sonic barrage that I got completely swept up by. I will never forget the first time I saw the Rangehoods because it was the first time I’d witnessed up-close, pure American rock played properly through the correct equipment, by four reckless rebels. I made sure it wasn’t too long before I befriended these hoods of the range.

As a young guy in Vancouver, I’d gone to see the great guitarist Amos Garrett, who in my opinion, played the most clever pop-music guitar solo of the 1970s on Maria Muldaur’s hit “Midnight at the Oasis.” As far as guitar solos go, it was so much smarter compositionally, that it towered above most of the other solos of its day. And there I was, standing next to the guy who played it. I was brave enough to ask Amos for some advice about how to get better and make something of myself on the guitar. He told me to go see everyone play, borrow anything I could from their playing, and try to sit in with them whenever they'd let me. When I first arrived in Seattle in the early 1980’s, I made it my mission to go out and watch all of the local bands, following the advice of Amos Garrett. From the older Seattle bands like Junior Cadillac and Kidd Africa to the younger guys like Billy Rancher and the Unreal Gods, The Visible Targets, or the great blues guitarist Isaac Scott. I chased them all down and absorbed what I could from them. I followed them all and usually ended up picking their brains about gear and influences or anything else that crossed our minds. Eventually I got to know some of these guys and was invited to sit in with them.

At the helm of the Junior Cadillac band was a guy name Ned Neltner. When I first got to town, Ned let me sit in with them at the old Fremont Tavern. Ned gave me enough time to play my heart out. I played all my best stuff early on, and soon my aching wrists started to give out. He was unexpectedly generous and his reaction to my playing was encouraging. A few years later, Ned formed a production company that was trying to make movies and records. Right around the time I first saw the Rangehoods, Ned and his partner were working on a movie project about the 1950’s rocker Gene Vincent. They were shooting a test film to try to sell their concept. In a weird coincidence, their script was based on a book written by my old friend britt haggerty, the drummer from the Honky Tonk Heroes in Vancouver, who never wanted his name capitalized. britt’s book was called The Day the World Turned Blue. It’s about the meteoric career and untimely death of Gene Vincent, whose song “Be Bop A-Lula” is a rock-n-roll standard. Ned asked me to come and be in the pilot film they were shooting. He said they’d be filming it down at the Moore Theater at 2nd and Virginia in downtown Seattle. He told me to wear 1950s clothes and to bring my Fender guitar. When I got there, I was pleased to see that Steve Pearson of the Rangehoods was also going to be one of the guys in the video. The video shoot went really well, and we all had a good time. It was attended by a crowd of folks from the Seattle music scene, and it was an honor to be part of a small film. I even got to be in a close-up. On a break, I went out the back door of the Moore to the loading dock in the alley and hung out with Pearson while he smoked cigarettes. We formed a friendship that day and started to get together every once in a while. Steve was restoring old Austin Healey 3000 sports cars. That was his job. It was a rare art form that he’d

mastered. He made a great living at it too. At his invitation I spent a couple of Thanksgivings with him at the home of his kind parents who welcomed me. I was an orphan in those days with no family in town. As time went by, I became friends with the other members of the Rangehoods too.

Steve and Don were part of a one-gig band I formed called The Vultures. It was a guitar instrumental group that focused on songs by the legendary Ventures, the most successful guitar instrumental band of all time, from the Tacoma area. I got the idea to pick songs from my favorite Ventures albums, Surfin’ and The Ventures in Outer Space. I’d come up with a nice set of the tunes and we played them at the massive Bumbershoot music festival at Seattle Center, in the shadow of the Space Needle. Don and Steve from the Rangehoods, as well as Craig Flory from The 57s, and Ernie Sapiro from the popular Seattle punky-rock band The Cowboys. Along with bass player Rolf Johnson, we all collaborated on this instrumental extravaganza, which was a smashing success.

Later, in the mid-1990’s, Bruce Hewes and Don Kammerer of the Rangehoods helped me build my first coffee shop, Gee Whiz, under the monorail in downtown Seattle.

Don was a gifted cabinet maker who built my main front counter cabinet and did some of the difficult finish work for me. Bruce worked as a contractor who helped me with building walls and putting in plumbing and flooring and stuff like that. He gave me the nickname “Browny” and would call me up once in a while so we could hang out and talk. I came to care about him a great deal. Bruce became a good friend. He was incredibly funny. He had a bunch of rock-n-roll stories from his years on the road. He had played in some big bands and had been on some big tours. I could be wrong about some of the details, but I heard that an earlier band Bruce played in with Pat Hewitt & Billy Shaw, called The Pins, played a bar in New Orleans once. They were supporting the great Cajun fiddler Doug Kershaw and they were rockin’ the joint in a big way. While they were playing, Bruce looked up and saw his bass- playing hero Bill Wyman and the rest of the Rolling Stones. They were all in the audience and really enjoying the show. Because of that, they ended up touring as an opening act for the Rolling Stones.

The Rangehoods were signed to a promotional contract with Miller Beer, along with some other big American bands such as The Blasters and Los Lobos. Miller made them posters, t- shirts, and other promotional items.

Bruce had a funny story for every tour he’d been on. Obscure phrases, jokes, and clever lines from old movies were some of his favorite social currencies. He thought it was cool that in a cheesy western he’d seen, when they were hanging a guy, they called it a “neck-tie party,” not a hanging. Often in an afternoon’s conversation, he would become funnier and funnier as the day wore on. There are legendary tales from fellow band members like Billy Shaw, who had to beg him to stop making him laugh as night turned to morning in some cheap gig hotel. My favorite Bruce-ism is, “It only costs a little more to go first class.” I have quoted that many times in my life, always giving credit to him.

Once we decided to be buddies, Bruce set up an extra bass amp in the basement of my house. He and a drummer friend of mine named Dov Friedman would jam together and record original songs. We had a regular schedule every Wednesday afternoon. It became a productive practice for us all. We worked on some of Bruce’s tunes too.

We all enjoyed each other‘s company and ended up laughing a lot. The amplifier that he left in my basement was a vintage Ampeg that was in beautiful condition. He loved it. One day he came over in his mint-condition 1967 Chevrolet Chevelle Super Sport convertible. Together we sat out on the front porch, admired his sparkly blue car, drank coffee, and had a very nice conversation. At one point he looked over at his car and realized that my cat Gandhi had climbed on, and was looking around inside Bruce’s car. In an instant he switched from a sweet and kind-hearted conversationalist to an enraged maniac who ran after my cat shouting and screaming. He was literally trying to catch and kill Ghandi. Of course, you could never catch a cat by yelling at it angrily. He was so mad about the cat getting on his car that it took me a while to calm him down and get him back to normal. I would never again leave my cat out when Bruce was around. Before he left that day, we planned to get together in the next couple of days to play some more tunes.

In the meantime, however, Gandhi acted nothing like his name-sake. He put two and two together with his incredible olfactory senses and figured out that the bass amp downstairs belonged to the same guy who had tried to chase him down and kill him. It wasn’t clear to me at first, but one day I noticed out of the corner of my eye, that Bruce’s amplifier looked a little bit different. I realized what Gandhi had been up to and how concentrated his efforts had been. Gandhi was in the revenge business now and he made it his mission to go down into the basement and spray Bruce’s bass amp with his funky cat spray every night. The foul stench of cat spray on anything is horrible. It’s even worse on a guitar amp because when it warms up and eventually gets hot, the stink permeates the whole area with foulness. Not long after I noticed this mess, Bruce called me up and in his raspy voice said, “Browny, I’m coming over to get my bass amp. I’ll be there in a half hour.” I had to clean that amplifier before he saw it or risk our friendship over Ghandi’s hijinks. It would take way more than a half hour, so I lied and told him I was just leaving the house and wouldn’t be back until late. I suggested he come and get it the next day instead. He was cool with that.

At this point I immediately got to work. I went down to the basement, took the amplifier apart, and cleaned every square inch of it to the best of my ability. Gandhi‘s crusty, crystalline spray had made it all the way through the grill cloth of the amplifier and onto the paper speaker material. It was a nasty-smelling disaster. I used warm, lightly soapy water and a toothbrush to gently scrub the cat spray off the speaker without soaking the paper and ruining it. I used the same method on the sides, top, and grill cloth of the old amplifier. It took me about four hours. In the morning I went and inspected it one more time to make sure it was OK. Everything was nice and clean. Now it was OK for Bruce to come and get it. He never found out that his amplifier had been sprayed by the cat that he hated so much. However, I wish this story didn’t take the turn it is about to.

A few weeks later, Steve Pearson called and told me that Bruce Hewes had been killed in a car accident. I was stunned. It was particularly tragic because he had just made it through a very difficult time dealing with some of his darkest demons. He had come out on the other side and was in really good shape and in a very positive frame of mind. The news of his death was devastating. I was overwhelmed by a deep sense of loss. I asked myself, What if I’d done something, anything to stop him that day, even for a moment? What if I’d kept him from that intersection of life and death? The questions friends and family always ask. It’s always too late and only magnifies the feelings of loss. We made a lot of good music together and shared a great friendship. I was terribly saddened. A pall fell over our corner of the Seattle music community. Bruce was widely loved, respected, and adored.

I knew Bruce’s brother Neal, and he gave me the details for Bruce’s funeral. There would be a service at a large church in Kenmore and a reception afterwards at the Kenmore American Legion. Kenmore is a town just north of Seattle on Lake Washington. Bruce and his gang were Kenmore boys, so it seemed fitting. I was invited to play some music as the first of several acts that would be playing at the reception. I gladly accepted. I had my Thompson acoustic guitar with me and went to the funeral at the big church. The church was packed wall to wall with some of the great rock musicians of Seattle.

Paul Allen, the cofounder of Microsoft, future owner of the Seattle Seahawks, and the fifth richest man in the world, was also there because he was Bruce’s friend. The audience was a Who's Who of Seattle music. There were a few famous guys and gals in the crowd that day and all of Bruce’s family members too. Sitting right up front were Bruce’s mom and brother Neal and some other relatives with their little kids whom I hadn’t met. The minister talked about Bruce’s life and his recent turnaround from hard times. After a while he asked if anyone would like to come up and share their memories of Bruce. One of the first people who went up to the lectern to speak was Bruce’s nephew who was about seven years old at the time. He had a small, three-foot section of picket fence with him that was painted white. This innocent little boy was filled with emotion and sadness. He held the small section of picket fence up and said, “This is part of the fence that I painted with my uncle Bruce.” The room was silent. The boy was sobbing when he began to talk about how much he loved his uncle Bruce and how sad he was that he would never be able to see him again. It was a powerful moment that touched us all. There was not a dry eye in the house. I get choked up even trying to retell the story. Everyone was crying, including myself. We could all picture Bruce taking the time, slowly and methodically showing his little nephew how to paint a fence, and we all felt how much it meant to him. Bruce’s little nephew and his raw feelings of sadness opened the waterworks for everybody. In his own way, he helped us all heal. He tapped into the grief trapped in all of our hearts. It was the most touching moment of release I’ve ever seen at a funeral. After him, some other people got up and spoke about Bruce. He had a lot friends there that day.

After a while, it seemed like things were winding down. The minister was wrapping things up and asked if there was anyone else. I was scared to raise my hand. Should I do it? Should I do it? I panicked for a second or two. I felt certain Bruce would be mad at me if I didn’t sing a song for him on this sad occasion. I could almost hear him saying “Browny...” So I gathered my courage and waved to the minister. I bravely walked up to the stage, opened the case, and pulled out my guitar. At first I was nervous to be amongst all of these great musicians. But I also had a clear purpose and was soon overtaken by a serene calm. I began to play a song I had written for my father called “Shine a Little Light.” The room went silent. It’s the last song on my Smoke Rings album and it’s a loving message that basically says if you get to Heaven before I do, please somehow shine a little light on me to let me know you’re OK. In the album version of the song, I mentioned my father’s old Mercury outboard motor. We had the old green motor from the 1940s on our little fishing boat when I was a kid.

The lyrics are, “What am I gonna do when I don’t have you to go fishing with? I bet that old Mercury is still running fine.” In a moment of inspiration I changed the song for Bruce to honor the memory of his life. Instead of Mercury, I said Chevy because of his beautiful hot rod. Anyone who knew Bruce knew how proud he was about his Chevy.

I sang the song with all the friendship and loyalty in my heart. I remained in tune throughout and finished without having made a mistake in front of a crowd of some of the greatest musicians in Seattle. I let go a huge sigh of relief as I strummed the final chord of the song.

To my surprise the entire audience stood up and cheered. They applauded in a loud, sudden burst of love for our departed friend. I’ve never had a more visceral reaction to a performance in my life. It was stirring.

That day I sang my song as an act of love for Bruce, his friends, and his family, but it mysteriously became a gift of love from Bruce to me. Not a day goes by where I don’t miss my dear pal Bruce Hewes. He was the coolest, most rock-n-roll friend I ever had. Everyone in that church that day would say the the same thing.

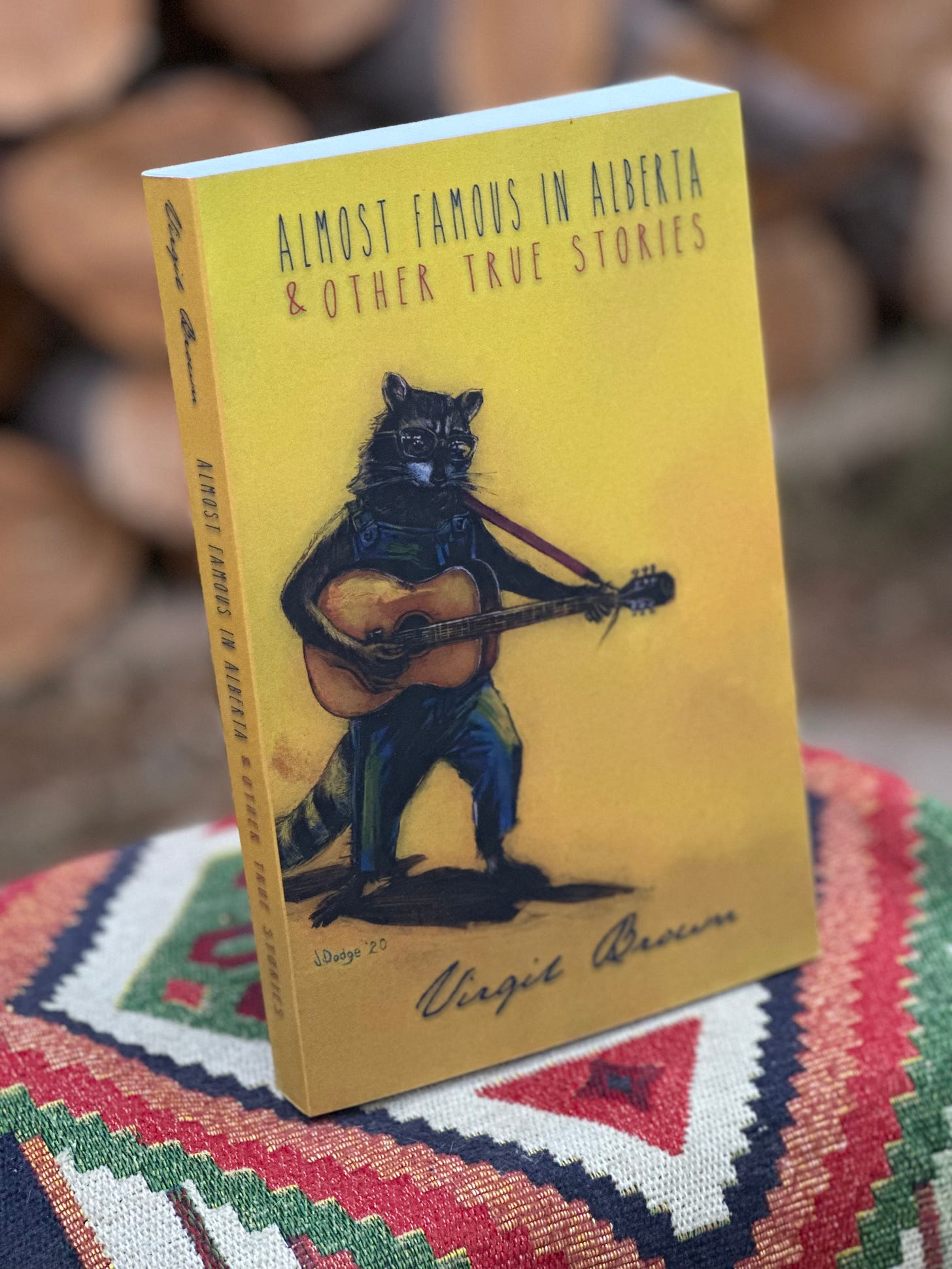

Today’s story comes from chapter 23 of the book I’ve written called: Almost Famous in Alberta & Other True Stories, available in paperback or on kindle at Amazon.com Be sure to support my old friends from The Rangehoods by buying their albums and streaming their music in all the usual places.

I’ll be out on the road again this year and I hope our paths cross somewhere on my Lost Highway Tour ’24. The number of shows is growing and you can see where I’ll be, on my website virgilbrownmusic.com if you clic the Shows tab.

It will be a tour of House concerts, Folk Music festivals (hopefully,) acoustic music venues and performance halls. If you, or one of your friends would like to host a House concert, check out the house concert guide on my website to see if such a thing would suit you. If you visit my website you wont go away empty handed, because you can download a number of my albums for free. If you enjoyed this presentation, check out some of my other podcasts by clicking the blogs and podcasts tab.

If you wish to support my endeavors, a paid subscription is less tha 20 cents a week a month and you’ll get extra content every now and then

Thank you very much! Goodbye…

Aw Stacy, thank you for the kind words. It was tough to get through the recording of the audio version without bawling. Many takes were required!

Virgil, I enjoyed this blog immensely. Thank you for the walk down memory lane and for riding about the Seattle music scene back in the day. Tremendously interesting riding. Good luck on your upcoming tour. - Stacy